SOMERS, NY – The setting is an outlaw motorcycle race in the 1920s, depicted near the end of the Discovery Channel miniseries “Harley and the Davidsons,” and it’s where Harley-Davidson makes history. Not only is the race the first time its legendary “Knucklehead” engine gets tested competitively, but the scene also  shows Harley-Davidson sales manager Arthur Davidson approaching racer William B. Johnson with a proposition.

shows Harley-Davidson sales manager Arthur Davidson approaching racer William B. Johnson with a proposition.

“I was wondering … if you would like to be an official Harley-Davidson dealer?” asks a smiling, cigar-chomping Davidson, handing over a packet of paperwork.

“There’s not a single Negro motorcycle dealer in the country,” responds Johnson.

“Nope. Not yet,” replies Davidson.

Whether or not this exchange accurately represents how “Wild Bill” Johnson became the first African-American dealer for the iconic motorcycle brand – after all, TV dramas do take dramatic license in recreating long-ago events – there’s no disputing Johnson’s place in Harley-Davidson’s history. And it’s a history that is preserved inside Town Hall in Somers, N.Y., the Westchester County town just west of I-684 where Johnson operated his dealership for some 60 years.

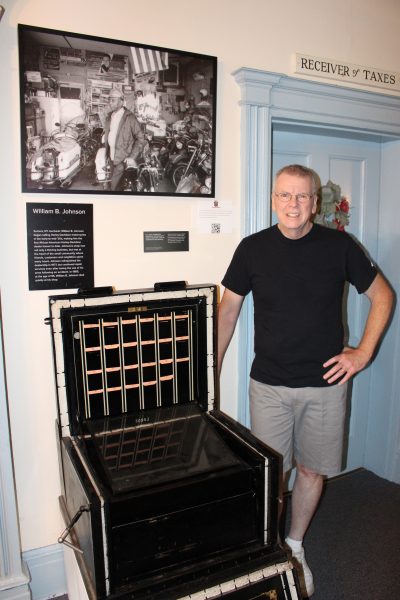

Inside the lobby of the former Elephant Hotel that now holds town offices is a display case with artifacts from Johnson’s racing days – goggles, leather helmet and leg gaiters. Sitting next to the display is a combination cash box and safe that once sat in the dealership a short distance away. Upstairs, on the third floor, is a racing suit that Johnson wore and the sign that hung above the door to his dealership.

Grace Zimmerman of the Somers Historical Society provided a tour recently, and invited former Johnson Harley-Davidson employee Tim Carney of Danbury to share memories of his ground-breaking boss.

“He was funny. He was very upbeat,” said Somers native Carney, who worked for Johnson between 1971 and 1975 and again from 1977 until 1979. As Carney talked, small details about Johnson’s life spilled out, gained through their many conversations over the years – such as how Johnson was Dodge car dealer before taking on Harley-Davidson.

Carney recalled that, as a youngster, Johnson lived in Maryland working as a “house boy” for a wealthy couple. “He did whatever they needed done,” he said. “The man died and the woman ‘freed’ him and gave him money. That’s how he came up here” and opened his business in a former blacksmith shop. “He was very appreciative of the woman because she basically helped him.”

Pictures of the shop, now the location of TJ’s Auto Repair at 280 Route 202, show cramped quarters and motorcycles packed in. In the early days, Carney said, “The motorcycles, when they came from Harley-Davidson, got delivered by train. They came to Purdys Station. He had a motorcycle with a sidecar frame that he turned into a flatbed.” New bikes were shuttled the two miles one by one.

A a young man, Johnson raced in hillclimbs nearby at what is now the Heritage Hills condo development. “He used to race on that hill as well as go out on the circuit,” Carney said.

How Johnson gained his American Motorcyclist Association license to compete is in dispute. The miniseries suggests that being a dealer, which sponsored riders, gave him access. But Carney confirmed lore that Johnson passed himself off as an American Indian to be admitted but also added that the hill’s owner wouldn’t allow it to be used unless Johnson could compete. Other historical data suggest influential citizens in Somers assisted.

While various online biographies of Johnson maintain that he gave up riding at the age of 82 after going down on his bike on an icy road and having both of his arms paralyzed, Carney said Johnson’s paralysis was actually due to botched surgery in the 1960s for a lump on his neck. “Everybody was telling him he should sue. He said it was a mistake. He said it was his lot in life and he accepted it. He felt it was something he shouldn’t sue over and he moved on. He was happy. He was not bitter at all,” Carney said.

During its heyday – Johnson Harley-Davidson lasted from the 1920s until 1977, then continued as a repair shop until his death – the store was a gathering spot for riders. “On Sundays, it was loaded with motorcyclists hanging out in front. It was the place to go for Harley riders,” Carney said.

Before and after being employed by Johnson, Carney worked at a Harley-Davidson dealership in Brewster and he used to come down on a motorcycle with a sidecar and take Johnson out for rides. “He loved it. That was his opportunity to be out in the wind,” Carey said.

Regarding Johnson’s place in Harley-Davidson and motorcycle history, Carney said, “Looking back, it’s just extraordinary.”

At the end of the feel-good conversation between Davidson (played by Bug Hall) and Johnson (played by Stephen Rider) in “Harley and the Davidsons,” Davidson pats Johnson on the back. The astounded racer asks, “Why me?”

“‘Cause you stand your ground. Because I believe every man should have the opportunity to make his good name,” replies Davidson before walking away, leaving Johnson close to tears of gratitude.

Johnson died in 1985 at the age of 95. For me, seeing his apparel and gear, being able to step inside the shop where he made motorcycle history, and hearing Carney’s reminiscences provided a memorable connection to history, and admiration for the motorcycle pioneer who lived it.

(Originally published in the “Republican-American” on Sept. 10, 2016.)

Ride CT & Ride New England Serving New England, NYC and The Hudson Valley!

Ride CT & Ride New England Serving New England, NYC and The Hudson Valley!