Riding through Olympia Pass in Peru

Rene Cormier jokes that the 2003 BMW F650GS Dakar that he no longer rides has been “put out to stud.” It’s still on the road, though, being trailered to speaking  engagements so that it may be seen by other envious motorcyclists – riders who wish they had the time, cash and courage to do what he did. Between April 2003 and October 2008, Cormier put nearly 96,000 miles on the dual sport machine while on a worldwide trek. He rode through 45 countries in a no-frills journey that lasted 4½ years, with one year off to replenish his bank account.

engagements so that it may be seen by other envious motorcyclists – riders who wish they had the time, cash and courage to do what he did. Between April 2003 and October 2008, Cormier put nearly 96,000 miles on the dual sport machine while on a worldwide trek. He rode through 45 countries in a no-frills journey that lasted 4½ years, with one year off to replenish his bank account.

Cormier chronicled his adventures in the book “The University of Gravel Roads – Global Lessons from a Four-Year Motorcycle Adventure.” He now divides his time between  operating a motorcycle tour company, Renedian Adventures, that offers African safaris and traveling North America giving talks about his incredible journey. “We bring the motorcycle to all of the events. It hasn’t been cleaned. It hasn’t been washed since the end of the trip,” he said earlier this week, explaining that attendees like to see the BMW “as real, as uncleaned-up and as unsanitized as possible. It adds a nice level of authenticity.”

operating a motorcycle tour company, Renedian Adventures, that offers African safaris and traveling North America giving talks about his incredible journey. “We bring the motorcycle to all of the events. It hasn’t been cleaned. It hasn’t been washed since the end of the trip,” he said earlier this week, explaining that attendees like to see the BMW “as real, as uncleaned-up and as unsanitized as possible. It adds a nice level of authenticity.”

Cormier will be in Brookfield on Thursday for a 6 p.m. presentation at Max BMW. He  will also appear at Cross Country Cycle in Metuchen, NJ at 7 p.m. Friday and at Max BMW in Troy, NY at 10 a.m. Saturday. The events are free and all motorcyclists are welcome. In his presentation, he covers “how the idea got created, how I paid for it – the who, what, when, where and how.” He also dispels suggestions that such a journey has to be dangerous or expensive. “I had expected, and most people expected, much more trouble, violence, unsettlement. I expected more danger in the whole thing. This world is much nicer than we’re told,” he said.

will also appear at Cross Country Cycle in Metuchen, NJ at 7 p.m. Friday and at Max BMW in Troy, NY at 10 a.m. Saturday. The events are free and all motorcyclists are welcome. In his presentation, he covers “how the idea got created, how I paid for it – the who, what, when, where and how.” He also dispels suggestions that such a journey has to be dangerous or expensive. “I had expected, and most people expected, much more trouble, violence, unsettlement. I expected more danger in the whole thing. This world is much nicer than we’re told,” he said.

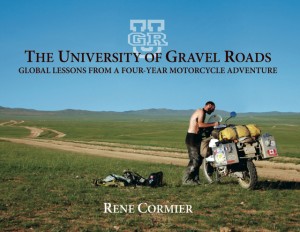

A roadside stop in Mongolia

His trip started and ended in Vancouver, British Columbia and took him through Central and South American, Africa and Asia. “Nothing was stolen from the motorcycle; no threat of personal injury. That flies on the face of what most people expect when they show up for the talk,” said Cormier, who is a native of Edmonton, Alberta.

One of the gas tanks on his BMW did get punctured by a bullet – the shot coming not from a bandito in some drug-producing country, rather in the United States. Specifically, Utah. Cormier said he had been looking for some hot springs on Bureau of Land Management property when night arrived. He bedded down beside the bike but was awakened around midnight by a “loud crack.” He turned on the BMW’s headlight to discover fuel coming from a dime-sized hole in one of the bike’s gas tanks as well as taillights disappearing in the distance.

Riding in Lake Turkana in Kenya

Riding in Lake Turkana in Kenya

Come morning, Cormier went the local sheriff’s office where it was suggested that the culprits might have been bored kids. “What I think happened was they saw what they thought (from a distance) was an abandoned motorcycle. He hit it pretty much dead center,” Cormier said.

Getting the plastic tank welded was one of the few repairs required during the trip. “Luckily, the bike was mostly problem-free throughout the entire trip,” he said. There were, as expected, some flat tires to fix, and he would “learn along the way.” In Mongolia, a water pump shaft seal failed and he had to replace it. “I was kind of glad it went. I had been carrying the bloody part for four years,” he said.

Camping in Mongolia

Cormier’s goal was to accomplish the journey on $25 per day. He funded the adventure by selling his house and most of his possessions. “I wasn’t a trust fund kid,” he said, explaining that a $9,100 annual budget covered food, gas, insurance and the cost of shipping the bike from South Korea back to the U.S. “Part of the strategy for surviving is to pick countries that are inexpensive,” he said. That meant avoiding Europe.

He began his adventure at age 33 and his biggest take away was that “big trips don’t require big budgets all the time. The simpler my life was on the motorcycle, the easier it was to enjoy. Everything I needed to be happy for five years was in a 12-square-foot box,” he said, referring to the bike’s footprint.

Two ways for avoiding problems were to talk with other travelers who were coming from places where he was headed and to stay up on the news. Danger is “largely avoidable,” he said. “What often helps the case is if you’re not in a rush to get from point A to point B. Time will get you much further and safer.”

When confronted by a week of bad weather, for instance, he’d hole up for a week and do bike maintenance and work on his diary. “Time is awesome, money is helpful,” he said.

It was while riding through in South Africa in 2006 that he met another rider who invited Cormier to stay at an apple farm that he owned. The guy’s wife was catering a party at a nearby farm and Cormier went along to help with the chores. At the party, he met a girl named Colette. They married in 2010 and now have a 15-month-old son.

It was while riding through in South Africa in 2006 that he met another rider who invited Cormier to stay at an apple farm that he owned. The guy’s wife was catering a party at a nearby farm and Cormier went along to help with the chores. At the party, he met a girl named Colette. They married in 2010 and now have a 15-month-old son.

Looking back on the trip, Cormier said his preparation was lacking in one area. He wishes he had taken language lessons, notably Spanish, before departing. “It’s so worthwhile to be able to converse,” he said, although by the time he made it to Argentina he was fairly fluent.

Cormier completed his solo adventure without sponsors and without any support vehicle. It was just him, his bike, the elements and the roads. “When you get to the end of it that reward; that feeling of accomplishment is entirely yours – a very delicious and addictive feeling,” he said.

(Originally published in “The Republican-American” on March 1, 2014)

Ride CT & Ride New England Serving New England, NYC and The Hudson Valley!

Ride CT & Ride New England Serving New England, NYC and The Hudson Valley!