Besides being a 1909 graduate of Cornell University and an astute mechanical engineer, Norbert Schickel was also a pack rat. Even after his Connecticut-based  business went out of business, the self-described “born mechanic” retained financial statements, contracts, photos, correspondence, schematics, promotional literature and even parts from his creations.

business went out of business, the self-described “born mechanic” retained financial statements, contracts, photos, correspondence, schematics, promotional literature and even parts from his creations.

“Grandpa never threw anything away, or very little,” according to Ken Anderson, and that proved to be immensely beneficial when the Olean, NY resident set out several years ago to write a book about his grandfather’s company that operated in Stamford from 1911 to 1924.

Largely forgotten today, the Schickel Motor Company built motorcycles, and was responsible for several innovations that were so useful or groundbreaking that other manufacturers, notably Harley-Davidson and Indian, stole them. Those competitors were later forced to pay damages for patent infringement and royalties for their subsequent use.

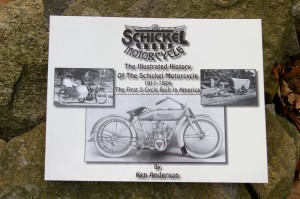

Schickel died in 1960 when Anderson was 17 – too young to appreciate his grandfather’s impact on motorcycling – but thanks to the hundreds of artifacts that still exist he was able to write “The Illustrated History of The Schickel Motorcycle 1911-1924.”

The self-published book offers a glimpse into motorcycling’s early days. It also conveys the civility of the times thanks to the eloquent letters contained within its nearly 200 pages.

While only a few American-made brands exist today – notably Harley, Victory and Indian, the latter two owned by Polaris – there were more than 100 motorcycle manufacturers in the U.S. early in the 20th Century.

“It was kind of amazing. Once people started moving to the city, the horse became obsolete. Where were you going to keep a horse? The motorcycle made the most sense,” said Anderson in a phone conversation from his home.

Cars were too expensive for most people and roads were nothing like those of today; more enhanced paths than smooth slabs. As a result, motorcycles became popular and evolved from crude to complex in a span of a few years, and that includes those made by Schickel.

“Look at a 1912 and a 1915, you feel like there’s a 20-year difference in improvement and design,” said Anderson. “A lot of sophisticated design went into the early motorcycle industry.”

Schickel actually began designing his first motorcycle while still at Cornell. Upon graduation, though, he went to work for luxury carmaker H.H. Franklin Manufacturing in Syracuse but only stayed with the company for less a year, moving back to his native New York City to continue work on motorcycle designs.

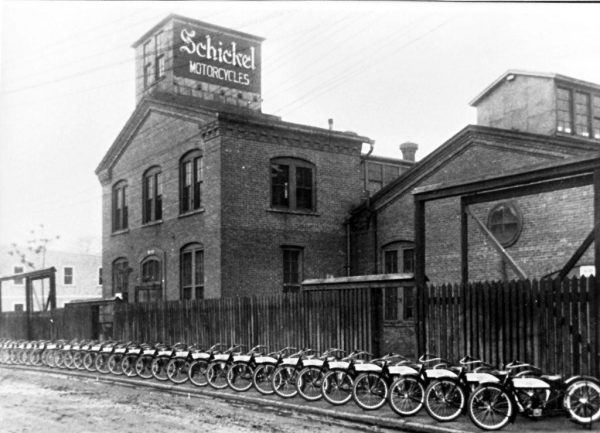

“New York City was too pricey and wasn’t set up for what he wanted to do and he ended up in Stamford,” Anderson explained. The factory was located at 55 Garden Avenue and produced about 100 motorcycles in both 1912 and 1913. The first motorcycle featured a five horsepower, single cylinder, two-stroke engine and sold for $225. The 30.25 cubic inch power plant was capable of pushing the bike up to 50 miles per hour.

“In 1913, he added a Big Six (model), which went up to six horsepower. He offered a belt drive and chain drive. By the time he got to 1914, the bottom fell out. That’s about the time Henry Ford reared his ugly head with the assembly line,” Anderson reported. By taking only 93 minutes to build a Model T and by dropping the price to $440 in 1915, Ford made automobiles affordable for the masses, effectively dooming most motorcycle companies.

Anderson said Schickel attempted to fight back by introducing the Lightweight model in 1915. The 12.25 cubic inch, 2½-horsepower bike sold for $99. “It got about 90 miles to the gallon,” he said, noting that high mileage was important because “there were not too many places to fill up.”

The Lightweight wasn’t without its idiosyncrasies. “The thing that was kind of interesting about those Lightweight models was that there was no transmission. You had to stall it to stop it, and give it a push to start it,” Anderson said, recalling that years later he became so proficient riding it that “I could basically stop at a stop sign and continue without having to wait” – kind of like doing a pause and go today without having to put your feet down when riding a motorcycle.

Other factors besides the Model T contributed to the demise of the Schickel Motor Company. Roads improved. Soldiers in World War I who had driven cars, trucks and tanks retained their automotive interest when they came home. Also, unlike Harley and Indian, which targeted a rougher riding crowd, Schickels were aimed at families.

In all, Schickel only produced about 1,000 motorcycles. Anderson doesn’t have a firm idea of how many still exist today, although his brother Bill has two 1912 models and sister Joan has two 1913s.

“The only other one I know about is a collector in Texas,” he said. “You never know if  someone’s going to find one in a barn somewhere. I’m sure there’s not many more.”

someone’s going to find one in a barn somewhere. I’m sure there’s not many more.”

Because of his book, the Schickel name will live on, celebrating the innovations of his grandfather, among them the first two-cycle motorcycle built in the U.S., the rotating magneto spark advance, the twist-grip transmission control, the spring front fork suspension, the drive shaft flywheel and the hinged rear mudguard.

It was Indian that swiped the spring fork design and ended up paying 15 cents each for patent infringement on 10,000 motorcycles, plus $250 for a license to use the patent. It was Harley that pilfered the rear fender design and ended up paying 10 cents each for 40,000 motorcycles, plus a $1,000 licensing fee.

While Anderson grew up knowing of Schickel’s contribution to motorcycling, he didn’t come to comprehend his impact until he was an adult and it was too late. “Unfortunately, I never really had a chance to talk to my grandfather about it,” he said. “I wish I had.”

In November 2011, Norbert Schickel was inducted into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame in Pickerington, OH.

Ride CT & Ride New England Serving New England, NYC and The Hudson Valley!

Ride CT & Ride New England Serving New England, NYC and The Hudson Valley!