CHESTER, VT – During the off-season, motorcyclists are free to dream about the perfect ride. My version of that ride involves clear, dry air; bright sunshine; and paved country roads through hilly country. I’ve been fortunate enough to live that fantasy many times up here in  Vermont as well as in Northern California.

Vermont as well as in Northern California.

With perfect conditions, you must have the perfect machine beneath you, with instant responsiveness to every input – to the point where it feels that if the bike is an extension of you. I can recall a day and a motorcycle that nearly achieved it all. It was an old Triumph Tiger, a 650 with a single Amal carb as opposed to the Bonneville that had twin carbs and a bit more power. However, the Tiger suited me just fine. I was trying the bike out with an eye to purchasing it from Brian Jones, a great guy who is no longer with us.

There is a section of road on Howe Hill in Pomfret, VT that is cut into the side of a hill with fabulous on-camber turns all the way up its flank. There are few things more satisfying than climbing through challenging curves with the power band exactly where you want it. On one especially tight curve I decided to downshift for a bit more oomph right in the corner’s apex. Instead of powering out of the turn, I nearly high-sided the bike as the rear brake locked up. What happened? Instead of downshifting, my left foot stomped the rear brake pedal. On this particular motorcycle, the shifter and brake pedals are on the opposite side from the typical American or Japanese motorcycle. Out of habit, I automatically defaulted to what I was most accustomed to. It nearly cost me an ugly accident.

Needless to say, I took a pass on purchasing the Triumph Tiger. Had it been intended as my only ride, I probably would have gone for it because I knew I’d be able to adapt. However, with another bike in the stable that had the controls mounted on the opposite side, I knew I would probably keep making this pedal mistake.

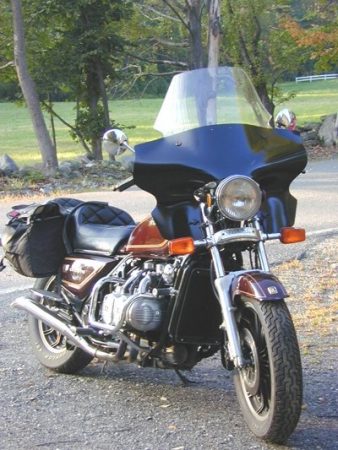

I never forgot all of the positive aspects of that great handling Tiger. On cold winter days, I would often think back to the experience of that one ride. After owning a BMW R100RT for many years, I decided to experiment with something completely different. I ordered a brand new 1999 cobalt blue Harley Davidson Sportster. With a pipe upgrade and a carb re-jet, it felt nearly as good as that old 1969 Triumph Tiger in the corners, albeit with a bit more vibration and clunkier shifting. In the time that I owned the Sportster, my biggest disappointment was its lack of power while riding two-up in hilly country. It just didn’t have it. So after a couple of years, I decided to experiment again. I sold the Harley and bought an old friend’s naked Honda Gold Wing. It was powerful enough, but after a while, I felt that it was just too tall for my limited inseam, so I sold it on.

My next experiment was a Harley Electra Glide Standard with a hot cam in it. I was really impressed with the acceleration for such a huge motorcycle. I kept it for a couple of years, got bored with it, and let it go. The next test was a naked sport bike. It was an emerald green Suzuki Bandit 1200. I gussied it up with an aftermarket windscreen and a beautiful tan Corbin leather seat with emerald green piping. The handling was superb, and the power was truly intoxicating. One day I got behind four cars just leisurely cruising on Vermont Route 30. I decided the pace was a bit too slow for me so I passed all of them on a single flat. Looking down at the speedo I realized I had gone well into the triple digits. I had been doing a fair amount of that type of riding and I started to feel that my road manners were too aggressive. When that particular riding season ended I decided to get back into the Harley fold and ride something that had a more laid-back feel to it.

I continue to try different things, experimenting with a dual-sport bike and a mid-nineties Honda Nighthawk, my trusty Bonneville and my best all around bike, the Harley 1200 Sportster. All of this fickle motorcycle ownership is due to experimentation, and my willingness to try new things. I don’t regret any of those former bikes. They all had a lesson to impart, and the gist of it is this; every motorcycle has its own purpose, and there really aren’t any motorcycles out there that can do it all. You can come close, but I’ve concluded that you need to have more than one at any given time to satisfy the varied demands of the active rider.

Ride CT & Ride New England Serving New England, NYC and The Hudson Valley!

Ride CT & Ride New England Serving New England, NYC and The Hudson Valley!